Biodiversity

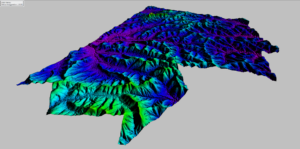

The composition and structure of dry forests—encompassing factors such as density, basal area, canopy height, and stratification—exhibit remarkable variability largely influenced by the type and history of human interaction. These forests are characterized by trees with thick, rough bark, short trunks, and deep root systems adapted to arid conditions. The leaves of these species are highly variable, with a significant presence of legumes featuring compound leaves, and many species possess thorns. During the dry season, trees employ a survival strategy by shedding all their leaves to conserve scarce water resources.

The diversity of plant species in these dry forests is particularly notable, with approximately 80% of the vegetation being endemic. This high level of endemism makes these forests crucial indicators for the identification and monitoring of environmental changes, reflecting the dynamic interactions among the various components of the ecosystem (Muñoz, Armijos-Ojeda, & S. Erazo, 2019). The most prominent botanical families in these environments in Ecuador—as well as in other neotropical dry forests—include Bombacaceae, Cactaceae, Boraginaceae, Moraceae, Malvaceae, Bignoniaceae, Bixaceae, Capparaceae, Fabaceae, Nyctaginaceae, Rhamnaceae, Salicaceae, Sapotaceae, and Theophrastaceae.

Many species in these forests have developed extremely extensive root systems that allow them to access nutrients at various soil depths; in some cases, these roots can extend over 100 meters. Certain tree species, especially emergent ones, have evolved by developing buttresses on their roots—large and thin extensions of the trunk that emerge about six meters above the ground. These structures are believed to aid in water capture and storage, increase the surface area for gas exchange, and accumulate leaf litter, providing additional nutrition. Similarly, some trees, particularly palms, possess stilt roots that offer additional support, effectively adapting to the challenging conditions of the dry forest habitat.

In the southern forests, the vegetation is dominated by guayacanes (Tabebuia chrysantha, Handroanthus chrysanthus) and ceibos (Ceiba trichistandra), which are large, barrel-shaped trees characteristic of the region. Other significant species include palo santo (Bursera graveolens), muyuyo (Cordia lutea), various acacias (Acacia spp.), and espinos (Pseudobombax millei). These species not only define the landscape but also play vital roles in the ecosystem’s health and resilience.

The exceptional biodiversity and high endemism of these dry forests underscore their ecological importance. By serving as crucial indicators of environmental change, they reflect the dynamic interplay between climate, soil, flora, and fauna. Protecting these forests is essential—not only for preserving the unique species they harbor but also for maintaining the ecological balance and supporting the livelihoods of communities that depend on them.

Understanding and conserving these ecosystems require collaborative efforts. By promoting research and sustainable management practices, we can ensure that these remarkable forests continue to thrive, offering invaluable insights into biodiversity and ecosystem functioning for generations to come.

Figure. Ceibo (Ceiba trichistandra) at Anna Lotte Reserve forest.